Hey what’s up. Earlier this week, Vox published an article called “The tech billionaires are missing the point of their favorite sci-fi series.” The titular tech billionaires here are Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, and Mark Zuckerburg, and the sci-fi series is Iain M. Banks’ Culture novels. I’ve been looking for an opportunity to write something about the Culture and its apparent influence on a certain type of tech guy, and this seems a good time to do that.

The article, by Constance Grady, is pretty brief, and it does give a nice overview of a few instances where Musk, Bezos, and Zuck have explicitly mentioned or referenced Banks’ work. Musk gives his drones fun little names, just like in the Culture. Haha. What the piece doesn’t do, in my view, is explain what it is about the Culture that is so attractive to a certain kind of tech guy. This is too bad, because the particularities of Banks’ vision of a post-scarcity utopian society, and the apparent attractiveness of that vision to guys like Musk, actually provide some interesting insight into how those guys understand their relationship to the world around them.

So what I want to do in here is talk a bit about the political climate of the late 80s and how it may have informed the politics of the Culture, and then circle back to the “tech right” and suggest a few ways in which Banks’ utopian vision might resonate with them.

To be clear I’m not trying to dunk on the Grady piece. Its broader position—billionaires are bad and the things that they like are made by people who don’t like them—is an idea with which I’m broadly sympathetic. Iain M. Banks himself was indeed a noted supporter of socialism, and the fact that a bunch of billionaire tech guys are talking about how they love his books would probably strike him as kind of grimly funny.

But her piece is a useful jumping off point for my purposes here because, in its insistence that “nearly every aspect of the Culture seems to be diametrically opposed to the worldview of the tech right,” it’s forced to give a fairly cramped and superficial account of Banks’ utopian vision and also a sort of odd interpretation of how the tech right actually views the world.

Because while it is nominally true, as Grady writes, that in the Culture, “there is no money…therefore, there can’t be any billionaires,” I’d posit to you that Banks’ vision of a techno-utopian anarchistic society governed by artificial intelligence, where people can live forever and are free to indulge all of their weirdest and most hedonistic personal desires, can actually provide a fairly insightful framework for understanding the priorities and interests of right-wing tech guys here on earth in 2025.

Liberalism, Utopia, and The End of History

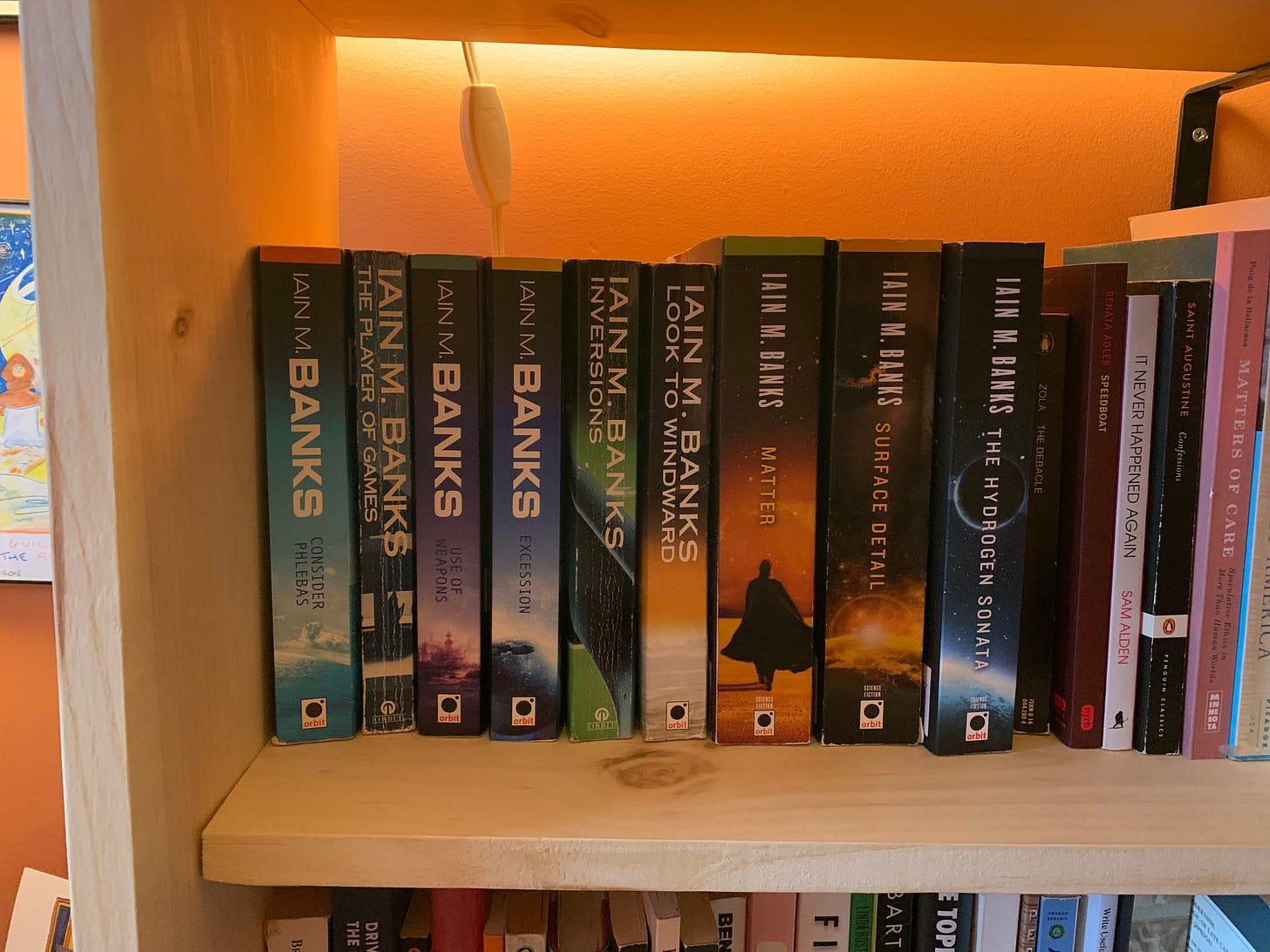

The Culture is a series of nine novels plus one short story collection written by Iain M. Banks and published by Orbit Books between 1987 and 2012. Each novel is its own self-contained narrative, and while there are a handful of characters that show up in multiple books, the main throughline of the series a whole is the Culture itself, a post-scarcity society that is managed by artificial super intelligences known as Minds. The Culture is made up of a distributed network of massive habitats known as Orbitals, and then a bunch of ships of various sizes. The largest type of these ships, known as General Systems Vehicles or GSVs, can house billions of people each, just to give a sense of scale. Every orbital and ship has its own Mind, and each Mind manages the various ship systems, plus attends to the needs of its inhabitants, the humanoid citizens of the Culture who are free to just kind of do whatever.

This freedom is really crucial to the whole project of the Culture. We might characterize the Culture as a sort of technologically-enabled liberal utopia. Crucially, though, it’s a utopia that’s been delivered through technological advancement rather than class struggle. This is really important to keep in mind, because by the late ‘80s, when the first Culture novels were published, some people had already begun to suspect that conventional politics was kind of out of gas anyway.

This newsletter has explored this period pretty extensively through the lens of Fredric Jameson’s Postmodernism, in which we find Jameson working through the collapse of the utopian impulse under the cultural logic of late capitalism, but the other more obvious touchpoint for this kind of thing is Francis Fukuyama’s essay, “The End of History?”, in which he posits that historical progress, or the Hegelian series of ideological struggles that moved societies from one period to the next, had reached its final stage in the Western liberal democracies of the late 20th century, and it would just be a matter of time before the rest of the world reached the same “conclusion.” A better world is not possible! This is as good as it gets!

What Banks is able to do in the Culture series is transpose this same basic logic—history has a conclusion and we’ve reached it—onto a futuristic society that, thanks to a bunch of technological advances, could be more plausibly seen as a kind of end state for civilizational development. This serves as a major animating factor for the Culture’s various interventions into other civilizations, which, as Grady notes, is usually what drives the plot for each individual book in the series. This tendency toward intervention, it should also be noted, sits at odds with the Culture’s foundational commitment to liberalism. In her book Bodies of Tomorrow, Sherryl Vint sums all of this up really nicely:

the most problematic aspect of the Culture is its belief that its moral perspective is so enlightened as to entitle it to interfere in the domestic affairs of other civilizations in order to ‘encourage’ these civilizations to move toward an ethic that more closely matches that of the Culture…the struggle to reconcile this perspective with the liberal humanist belief in individual freedom, a struggle that is also part of the ‘real world’ history of liberalism and its connections to colonialism and the suppression of other cultures, dominates these works (85)

Escape from Politics

So this tension between liberalism and interventionism expresses itself throughout the Culture series a bunch of interesting ways, both in terms of how the Culture interacts with other civilizations as well as its own internal structure. To pick an example from the Vox piece, for instance, Grady writes that “in the Culture, should someone commit an action that most people agreed was unacceptable, everyone responds with social shaming rather than the rule of law: They stop inviting the person in question to parties. In other words, like a group of proper leftists, they deal with misbehaviour by social cancellation.”

What she’s not mentioning here is that beyond social pressures, criminals in the Culture are also assigned what’s called a “slap-drone,” or a little drone that follows them around and stops them from committing further crimes, in some cases by force. The authority that informs these assignments is instructive, because it provides a neat little justification for one way in which the tension between liberalism and interventionism can be resolved: In Surface Detail, an avatar for one of the Culture’s Minds describes the authority by which they could impose a slap-drone on someone: “ultimately my right to impose a slap-drone on you comes down to the principle that it is what any set of morally responsible conscious entities, machine or human, would choose to do were they in possession of the same set of facts as I am” (155). It’s an attractively neutral bit of reasoning: I’m a super intelligent computer, and my actions are reflective of a certain responsibility imposed by my awareness of this situation. The correct course of action just sort of falls out of the basic facts: It’s fundamentally impersonal and apolitical.

This basic line of thinking strikes me as fairly similar to a lot of the AI enthusiasm coming from the Tech Right. Musk himself has already tweeted about the possibility of his own LLM, Grok, rendering “extremely compelling legal verdicts” after he finishes “adding all court cases to the training set.”

Along these same lines, I’d argue Banks’ whole techno-utopian vision provides a kind of model for something that’s been a longstanding project for the Tech Right. Here’s an excerpt from an extremely sinister essay that Peter Thiel wrote in 2009:

In our time, the great task for libertarians is to find an escape from politics in all its forms — from the totalitarian and fundamentalist catastrophes to the unthinking demos that guides so-called “social democracy.”…The critical question then becomes one of means, of how to escape not via politics but beyond it. Because there are no truly free places left in our world, I suspect that the mode for escape must involve some sort of new and hitherto untried process that leads us to some undiscovered country; and for this reason I have focused my efforts on new technologies that may create a new space for freedom.

Compare that to Banks’ own description of the formation of The Culture, from an essay he wrote in 1995:

The Culture is a group-civilisation formed from seven or eight humanoid species, space-living elements of which established a loose federation approximately nine thousand years ago. The ships and habitats which formed the original alliance required each others' support to pursue and maintain their independence from the political power structures - principally those of mature nation-states and autonomous commercial concerns - they had evolved from.

A loose federation with the shared goal of maintaining independence from the power structures of mature nation-states. Familiar, right?

My sense is that this is exactly what the Tech Right sees in the Culture series: a vision of the future in which a post-scarcity utopian society just kind of spontaneously emerges through the force of technological development alone, where history has still ended and existing political institutions can continue to atrophy while a few clever tech guys sneak out the side door and head toward the stars in a cool spaceship with a funny name.

To put all of this in more comfortable Jamesonian terms, here’s a nice quote from Archaeologies of the Future:

The Utopian form itself is the answer to the universal ideological conviction that no alternative is possible, that there is no alternative to the system. But it asserts this by forcing us to think the break itself, and not by offering a more traditional picture of what things would be like after the break…The formal flaw - how to articulate the Utopian break in such a way that it is transformed into a practical-political transition - now becomes a rhetorical and political strength - in that it forces us precisely to concentrate on the break itself: a meditation on the impossible, on the unrealizable in its own right. This is very far from a liberal capitulation to the necessity of capitalism, however; it is quite the opposite, a rattling of the bars and an intense spiritual concentration and preparation for another stage which has not yet arrived. (232-233)

Say what you will about the Tech Right, they do appear to believe that an alternative to the present political arrangement is possible. They have “thought the break,” in their own weird libertarian way, and we’re currently witnessing the results. Is the Left ready to do the same?

Okay thanks for reading. Next time we’ll go back to talking about A Singular Modernity.

So Musk has already caught himself a bit of the shaming. Wonder where his head’s at there. And, in order to advance his techno utopia he decided he should just shunt cash from the less fortunate to his particular .gov grift. How would Banks weigh in on that? As a humanoid on a biosphere called Earth, with the facts i have, i vote for much, much more shaming.