Hey what’s up. This is part 12 of my ongoing series summarizing Fredric Jameson's Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. To see previous entries in this series, check the archive. This part in particular is a summary of the final two sections (x-xi) of the Secondary Elaborations, the concluding essay of Postmodernism.

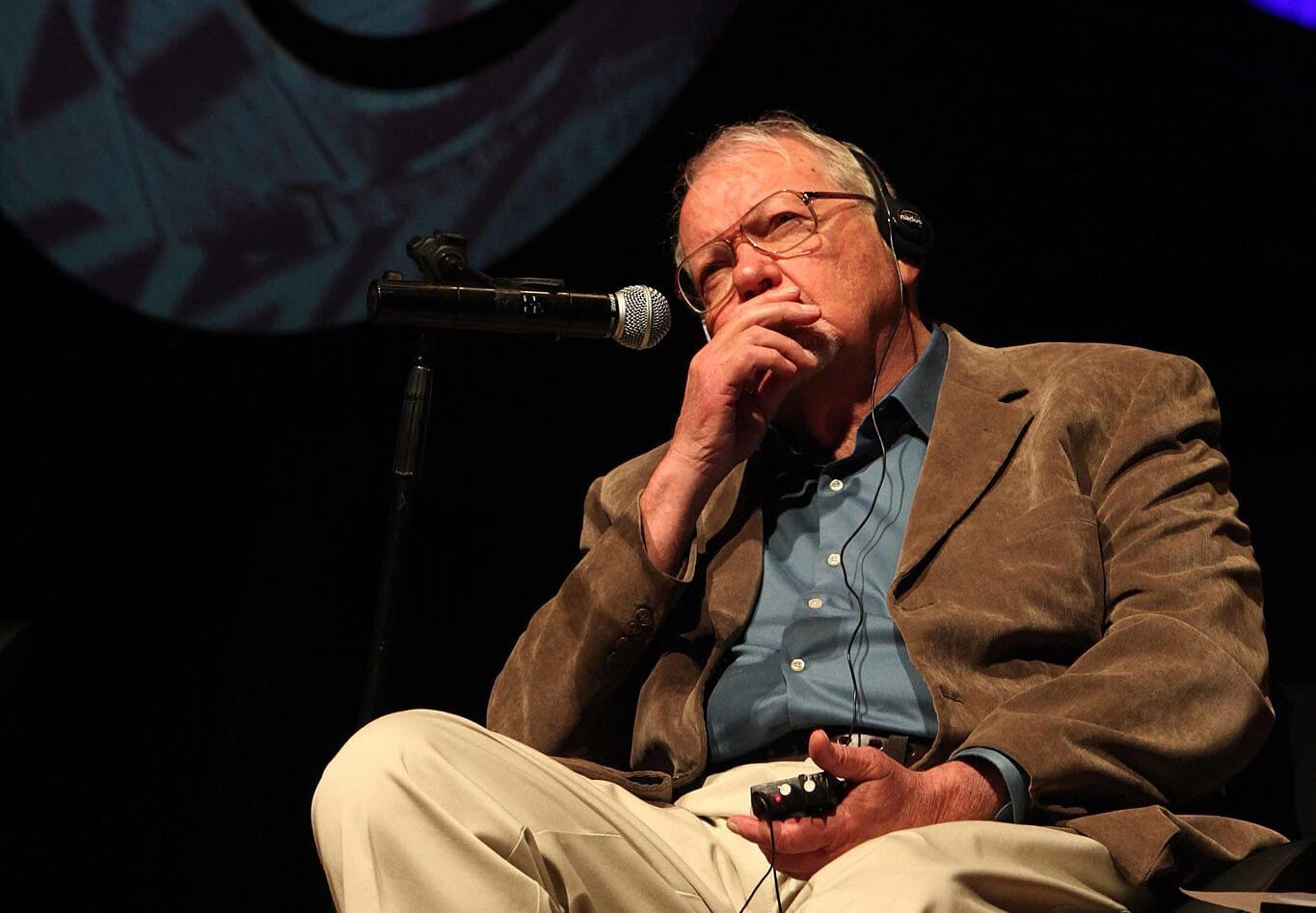

I’m returning to this project again in October of 2024, a week or so after the passing of Fredric Jameson. I don’t think my status as the preeminent Postmodernism summary guy on substack necessarily qualifies me to eulogize the man who wrote it, so I won’t attempt that here. I will just say Jameson loomed extremely large for me when I was in grad school, and I still find his work hugely rewarding to read and think about today. I can’t think of another writer who can pack more genuine insight into a single sentence, or who can make the study of literature feel more vital than Fredric Jameson. I liked Terry Eagleton’s piece for the LRB on Jameson and his new book a lot, and it was genuinely very moving to see people sharing memories of him on twitter. Someone said that he saw Jameson using a computer once and he would move the mouse around with two hands like he was using a ouija board, which is really good to think about. He really was the best to ever do it.

X. The Production of Theoretical Discourse

In the long chapter on theory, one of the takeaways Jameson offered is that post-structuralist theorists like the new historicists operated under the assumption that it was impossible to do theoretical work that “transcended” its particular historical moment. And so while there are a bunch of fun things you can do with the various ephemera of a particular period, it was all kind of trapped in that period, and you cant really extrapolate outward in any meaningful sense. Another way to phrase that, and how Jameson phrases it here in his secondary elaborations, is that post-structuralism is all about the impossibility of saying saying anything absolute. as a result, linguistic expression is reduced to “a function of commentary, that is, of a permanently second-degree relationship to sentences that have already been formed.” (393)

As discussed in that earlier chapter, this is a trap for postmodern theory guys, for whom “the mission of theoretical discourse thus becomes a kind of search-and-destroy operation in which linguistic misconceptions are remorselessly identified and stigmatized, in the hopes that a theoretical discourse negative and critical enough will not itself become the target of such linguistic demystification in its turn. The hope is, of course, vain” (392-93).

If you’ve spent a little time in graduate seminars you’re probably somewhat familiar with how this disposition toward theory looks and feels on a practical level. Every theoretical position or framing of a certain problem is always to the exclusion of something else, and no matter how careful or defensively you frame something, you’re always open to criticism from some other angle.

Jameson describes this situation in terms of “ideolects” and group adherence:

Where I used to ‘believe’ in a certain vision of the world, political philosophy, philosophical system, or religion as such, today I speak a specific ideolect or ideological code—the badge of group adherence, viewed from a different and more sociological perspective—which presents many of the features of an officially ‘foreign’ language (393)

You say climate change is “a struggle in the planetary factory” and I say “ah, but can indigenous land defenders be reduced to mere labourers in that factory” and everybody either nods or groans at my shit depending on their ideological, or uh, “ideolectical” affinity. It’s a classic Annoying Seminar Guy move. The reason why its annoying, in Jamesonian terms, is because you now find yourself having to contend with two different ideolects (in this case eco-marxism vs like postcolonial eco crit), neither of which can be fully reducible to the other.

It’s worth noting that this for Jameson a fundamentally linguistic problem, where two different discursive modes are clashing with each other. But its also tied up with identity in some tricky ways. If I’m framing my little argument in a way that implicitly excludes a postcolonial perspective, I’m leaving myself open to the (possibly bad faith but also possibly not) accusation of excluding colonized peoples, silencing them, rendering them unmournable, asserting some kind of epistemic privilege over them, etc. etc.:

If a code attempts to assert its nonoptionality—that is to say, its privileged authority as an articulation of something like a truth—it will be seen not merely as usurpatory and repressive but (since codes are now identified with groups, as the badge of their adherence and the content of their expression) as the illicit attempt of one group to lord it over all the others (397).

Still, Jameson offers a couple of generative ways of “doing theory” within what we might think of as an irreducible discursive landscape:

Under these circumstances, several new kinds of operations are possible. I can transcode; that is to say, I can set about measuring what is sayable and ‘thinkable’ in each of these codes or idiolects and compare that to the conceptual possibilities of its competitors; this is in my opinion, the most productive and responsible activity for students and theoretical or philosophical critics to pursue today. (394)

Some surprisingly practical advice here. And he’s right! This is a really good and generative way of doing theory, and you can get a lot of milage out of this approach. Simply take up a particular ideolect or discursive framework and evaluate what it can or can’t be made to say. Jameson has done this a lot throughout this book, and has continued to do a similar thing in the writing he’s published since. He’s built a real reputation out of being the guy who can take a whole discursive framework and say “here’s what it can and can’t do.” It’s what makes him great! It’s also kind of what makes him annoying to many people, I think. And we’ve seen examples of that throughout this project as well. He’ll take up some set of theorists (like the new historicists or the “new political movements”), pluck a few quotes, and say, here’s what they’re doing, and here’s where its limits are. As I mentioned before, this kind of thing sometimes operates on a level of abstraction that can feel a little bit dismissive of the work on its own terms. But if you’re a grad student and you’re looking for a way to frame out your dissertation, then a good faith engagement with some popular ideolect and its possible limitations is a reasonable place to start.

In any case, Jameson also notes that another operation available to contemporary theorists is “what I will call the production of theoretical discourse par excellence, the activity of generating news codes, it being understood that in a situation in which new ways of thinking and new philosophical systems are by definition excluded, this activity is utterly nontraditional and demands the inventions of new skills altogether.” (394)

So what does generating new codes look like under these conditions? Hard to say. Jameson admits that “the present remarks are only prolegomena and notes” toward some more robust theorization of what a meaningfully new discourse would look like. He gestures toward the work of Bruno Latour, who “has combined a semiotic code with a map of social and power relations to ‘transcode’ the scientific fact and the scientific discovery itself. Nothing, indeed, prevents the enlargement of the chain of equations to further codes”(395).

In fact Latour would go on to enlarge the chain to an insane amount of codes in his Inquiry Into Modes of Existence, which is this wildly ambitious project in which he aims to do the same thing he did with science studies to basically every other domain of knowledge. It’s a really fun book if you’re into this kind of thing, but I don’t know if it succeeds in quite the way Jameson is anticipating it might.

XI: How to Map a Totality

Anyway. Jameson’s insistence on the nonoptionality of Marxism is here returned to as another way to think about the present moment’s resistance to “totalizing” theorizations more generally. He writes, “It has not escaped anyone’s attention that my approach to postmodernism is a ‘totalizing’ one. The interesting question today is then not why I adopt this perspective, but why so many people are scandalized (or have learned to be scandalized) by it.” (400)

This has been kind of the central thread of this whole long final essay, and it does appear to be the grounds on which this confrontation that he’s anticipating between modernism (read: good old totalizing and historically-situated marxism) and the postmodern (with its inability to meaningfully recognize class and history) will be hashed out. Previously in this essay, he’d staged this tension in terms of a kind of utopian anxiety (wherein the postmodern subject intuitively shrinks away from confronting whatever lies beyond the grinding but familiar rhythms of life under late capitalism) as well as a vaguely psychedelic demographic anxiety (wherein wrapping one’s mind around the sheer volume of people that iteratively make up any meaningful accounting of “history” would be too much to bear).

But this confrontation can be staged in a third way as well, which has more to do with the how different historical moments seem more inclined to “totalizing” thinking than others. He writes, “The hubris of the present and of the living can be avoided by posing the issue in a somewhat different way: namely, why it is that ‘concepts of totality’ have seemed necessary and unavoidable at certain historical moment and, on the contrary, noxious and unthinkable at others” (402).

Smartly, Jameson sort of sidesteps the messy epistemic question about the limits of consciousness as such, and reframes the whole thing as a representative or discursive problem. So: the thinkability of a given historical moment from within becomes, somewhat more manageably, the meaningful representation of a historical totality in the context of a historical novel, which brings him back around to our old pal Sir Walter Scott (as interpreted by our other pal Lukacs.)

Scott, like Faulkner later on, inherited a social and historical raw material, a popular memory, in which the fiercest revolutions and civil and religious wars inscribed the coexistence of modes of production in vivid narrative form. The conditions of thinking a new reality and articulating a new paradigm for it therefore seemed to demand a peculiar conjuncture and a certain strategic distance from that new reality, which tends to overwhelm those immersed in it. (405)

This is all a kind of roundabout way for Jameson to offer a kind of justification for why, even though he’s going to insist that “Postmodernism” is properly understood as a “mode of production” rather than a kind of cultural phenomenon, he’s spent the bulk of his big book on Postmodernism looking at video art and books and other cultural artifacts.

This little turn initially feels like an odd little digression in so far as anyone who has read through the preceding hundred pages of these secondary elaborations, never mind the whole 300ish pages of book leading up to them, is probably more or less on board with the project here, but nonetheless Jameson is essentially defending the practice of literary or cultural analysis as such as a meaningful activity for understanding a particular historical moment.

Because I think there is a kind of ungenerous read of Jameson that would run something like this: His posturing about the non-optionality of marxism is just kind of typical theory guy rhetoric, but what he’s really doing is using the conceptual toolbox developed by marxist scholars as a heuristic for talking about the books and movies he likes, and sometimes that yields some interesting insights, because he’s a smart guy, but all of this stuff is happening within a broader sphere of like, “cultural commentary”, which even Jameson himself would insist is downstream from Politics as such.

But Jameson is going to insist that no, serious literary scholarship more broadly plays a functional role in rendering visible the contours of a particular historical moment (i.e., “mapping a totality”). Of course all of this is complicated by the fact that this act of mapping is very tricky indeed:

What is essential is that the culture ideology in question articulate the world in the most useful way functionally, or in ways that can be functionally reappropriated… There can surely be no model or formula give in advance for these historical transactions; just as surely, however, we have not yet worked this out for what we now call postmodernism. (407)

We have not yet worked this out. But he’s got some interesting ideas about where we might look. And if you’ve been following along with this project, it will perhaps not surprise you to learn that Jameson anticipates the map of the postmodern will be a spatial one. This is an argument he’s touched on in various ways already throughout this book, but the way he rehearses it here is really concise and illustrative, so let’s run through it to wrap things up.

The three stages of capitalism (classical, imperial, and late) have each generated their own unique type of space, which “are all the result of discontinuous expansion of quantum leaps in the enlargement of capital, int he latter’s penetration and colonization of hitherto uncommodified areas. A certain unifying and totalizing force is presupposed here—not the Hegelian Absolute Spirit, not the party, nor Stalin, but simply capital itself; and it is at least certain that the notion of capital stands or falls with the notion of some unified logic of this social system itself” (410).

The first of these spaces, which corresponds to the classical or market stage of capitalism, is a kind of grid, wherein the patchy and heterogeneous world of precapitalism becomes standardized, quantifiable, geometric, etc. Jameson points to Faucault’s Discipline and Punish as a useful short-hand for this kind of space, though obviously for Marxists the organizing principle of this kind of space is like, labor and production rather than Foucault’s slightly more mystified notion of “power”.

The notable thing here is that in this classic market stage of capitalism, the basic logic is still fundamentally localized. It’s the most basic version of capitalism, wherein your individual experience still largely overlaps with the entirety of the economic activity that structures that experience. Exchange value has replaced use value, but the market is a fully mappable physical space that you probably literally go to, and you can still more or less trace the production of the stuff you buy.

This stops being the case as we move into the second stage, Lenin’s “stage of imperialism,” wherein the economic structure expands far beyond individual experience. Here’s Jameson:

At this point the phenomenological experience of the individual subject—traditionally, the supreme raw material of the work of art—becomes limited to a tiny corner of the social world, a fixed-camera view of a certain section of London or the countryside or whatever. But the truth of that experience no longer coincides with the place in which it takes place. The truth of that limited daily experience of London lies, rather, in India or Jamaica or Hong Kong: it is bound up with the whole colonial system of the British Empire that determines the very quality of the individual’s subjective life. Yet those structural coordinates are no longer accessible to immediate lived experience and are often not even conceptualizable for most people. (411)

Edward Said’s Culture and Imperialism, in particular his essay on Jane Austen, have become kind of the standard touchpoint for describing this particular phenomenon, and Jameson himself will return to the issue of globalization and its impact on representation throughout his career—some of that writing has been collected in that Inventions of a Presentcollection from earlier this year. But his interest here in particular is about how this growing divide between individual experience and an increasingly complex economic reality results in the emergence of some idiosyncratic new strategies for mapping consciousness:

What we begin to see is the sense that each consciousness is a closed world, so that a representation of the social totality now must take the (impossible) form of a coexistence of those sealed subjective worlds and their peculiar interaction, which is in reality a passage of ships in the night, a centrifugal movement of lines and planes that can never intersect. The literary value that emerges from this new formal practice is called ‘irony’; and its philosophical ideology often takes the form of a vulgar appropriation of Einstein’s theory of relativity. (412)

He names Conrad and Pessoa as practitioners of this new kind of closed off and relativistic expression of consciousness, but you could also probably think of Kafka here: The big ironic punchline in The Metamorphosis tracks a collision between these previously sealed off subjective worlds, suggesting a social space iteratively constructed through a tense network of partial apprehensions. In general, though, there’s a really load-bearing assumption revealed here about the “experience of the individual subject” as the traditional “supreme raw material of the work of art.” You’ll see Jameson further unpack this idea and its implications for like the historical development of the novel in Antinomies of Realism, but the idea that Art as such is fundamentally a vehicle for the expression of individual experience struck me very powerfully on this read through of this essay, in part because I think it is really crucial for understanding how Jameson wants to position literature and cultural production relative to politics: They’re down stream and symptomatic, but also something more than that.

Finally, late capitalism takes this same network and kind of compresses it down:

The new space that thereby emerges involves the suppression of distance…and the relentless saturation of any remaining voids and empty spaces, to the point where the postmodern body…is now exposed to a perceptual barrage of immediacy from which all sheltering layers and intervening mediations have been removed (413)

This is potentially very uncomfortable, especially if you’re someone who has grown accustomed to sheltering layers and intervening mediations. But it’s also good, or at least potentially good, because in cracking open the “sealed subjective worlds” of the previous stage, things are suddenly moving again. There are new characters within frame, new pressures being exerted and rendered visible. For Jameson, this is an opportunity for the resurgence of a new kind of class consciousness. Here’s how he ends the essay:

“Cognitive mapping” was in reality nothing but a code word for “class consciousness” — only it proposed the need for class consciousness of a new and hitherto undreamed of kind…The rhetorical strategy of the preceding pages has involved an experiment, namely, the attempt to see whether by systematizing something that is resolutely unsystematic, and historicizing something that is resolutely ahistorical, one couldn’t outflank it and force a historical way at least of thinking about that. “We have to name the system”: this high point of the sixties finds an unexpected revival in the postmodern debate. (418)

So that’s Postmodernism! What a ride. Thanks for reading!